- Home

- Joe Denham

The Year of Broken Glass Page 26

The Year of Broken Glass Read online

Page 26

“What about the Nazis? Their barbarism was only enhanced by technology. What about nukes and chemical warfare? So we’ve acquired the means to spill off our aggression elsewhere. Folks send their sons and daughters overseas to do the dirty work nowadays so they can stay home and quietly hate their neighbours. What’s the difference?”

“I think you know what the difference is. Of course there will always be war. But it will be contained and restrained because we eventually won’t have the resources for it. As the natural world dies, we’ll be forced more and more to focus on our own collective survival. And this will in turn force us away from our tribalisms and nationalisms, toward a new ethos of cooperation because our self-interest will dictate it as such. The Nazis were like a bunch of five-year-old boys playing with loaded rifles. They’d come from the farm into the throes of modernity. They were out of sync, of two worlds. The further we move away from our agrarian past, the more comfortable we become with technology, the more control we attain. It’s evolution, Figgs. We’ll never be free of its growing pains. We’re not going to arrive suddenly or eventually at some state of enlightenment. But we’re learning with each generation’s advancements, and to wind the clock back, to take away the impetus of scarcity that is right now accelerating our mutual development, that will only lead to the prolonging of war and poverty as we know it.”

“And you’re certain of this, are you?” I stared into him as I said this, searching for any sign of doubt or falsity; of any ulterior motive at play, but I couldn’t detect any. I’ve seen all kinds of crooks and deceivers, and Jeremy Gibbon’s not one of them. As calculated and cold as his ideas are, there is a genuineness about him, even an earnestness. He placed his burnt-out cigarette in the tray and slid the cellphone to my far edge of the table, standing as he did so. “I’ll give you $500,000 if the information you supply leads the float to me or me to the float. It’s that simple. I haven’t the time or the inclination to seek out the float the way that Arnault does, and it is futile for me to try to duplicate the coverage the Children of Mu has. So I’ll let them locate it for me. And if you want the money, you’ll help me do this.”

“And if I don’t?”

“Then you don’t. And that’s your choice. You know I’m good for the money. And you should also rest assured that any violence which may arise as a result of all this will only be dictated by that which Arnault and his men may escalate it to in resistance. I have no intention of bringing harm to anyone. That being so, the men I have contracted to take care of this for me have their way of handling such things, and I will not be with them when the situation arises, so it will be out of my hands. If Arnault were a wiser man he would see the wisdom in what we have discussed. I’m of the mind that humanity should not be made victim to his stupidity, and if that stupidity brings about some casualties in the course of all this it will be greatly sad, but the casualties and the sadness that will result if he is allowed to do what he proposes to is a million times greater. I’ll do whatever it takes to keep that from happening. Do you understand, Figgs?”

I only nodded in response, as there was nothing more to say. It was clear these two men had declared war on each other and I was now caught in the crossfire, and my only choice was to walk away—to where though, and for what?—or choose which of them I’d stand beside.

That was a long time ago now, and it was the last I’d seen of or spoken with Jeremy Gibbon until I called him from Halfmoon Bay with the news of Fairwin’ Verge’s call to Arnault, and of Anna’s husband’s and Miriam’s imminent arrival in Hawaii. That phone call earned me my five hundred grand, and just as Gibbon promised, the money has been deposited in my account. That should have been the end of it, and if I were wise, or of greater means, it would have been. But I’m neither. And I have my ever-approaching old age to consider.

So when Jeremy Gibbon offered me another fifty thousand to keep the phone on standby, I took it. And when he offered me another hundred thousand for the whereabouts of Anna’s husband if and when I received that information, I took him up on it also, and I called him as soon as I was able to learn the EPIRB coordinates Anna found. I supplied this information with the understanding of course that he and Miriam would not be harmed, but now Anna’s husband has been picked up in the middle of the ocean floating half-dead in a dinghy. Miriam is nowhere to be found. I don’t know even if she’s still alive, and Anna’s husband has yet to speak. All I know is that if my actions have led Miriam to harm in any way I’ll never forgive myself. And I’ll hunt down Gibbon if it takes me to the end of my days. I’ve tried calling him and he doesn’t answer, which makes me all the more suspicious. If I were of a weaker stomach I’d be sick with what I’m feeling. There’s one thing I can’t stand and that’s being helpless. It’s against every fibre of my being.

Gibbon embedded a tiny magnetic tracking device in this phone. He didn’t tell me, of course, but I had the electronics guy in Parksville who works on all the boats, one of these ultra-geeks, check it over and he found it right away. You should have seen the look in his eyes, pure pleasure, at viewing such a high-tech little piece of tin and plastic. And you should have seen the look in mine. Because if there’s one other thing I can’t stand it’s being lied to, and Jeremy’s not telling me about that little thing amounts to as much. I should have tossed the phone right then and there, and I thought at least to remove the device, though I feared it might nullify our deal, and by then I’d already grown pretty warm to the idea of an extra half a million dollars padding my pocket.

But now Miriam’s gone and for the first time Jeremy is not answering my calls, and I don’t like what it adds up to. Since he brought Anna’s husband aboard Arnault has been steaming southward full throttle back toward Hawaii and I can only imagine he’s got some plan to recapture the float from Jeremy now that he has what he otherwise needs to fulfill the prophesy. And in thinking through all this it isn’t hard to imagine also that the phone I’m holding now in my hand puts myself and everyone on this boat suddenly in the realm of danger, which leads to the inevitable conclusion that I have to get rid of it, even if it might, in Gibbon’s eyes, negate my right to the funds I’ve already received. Even if it leads to his trying to recuperate them in the future. Five hundred and fifty grand, maybe more if he paid me for the EPIRB coordinates, which obviously didn’t lead him to Anna’s husband as I’d thought it would. I was in fact so sure it would that I baited Anna with the idea that the EPIRB had most likely been set off when Gibbon had found her husband and Miriam.

Fiery as Anna is, I knew she’d break the oath I made her swear to and go to Arnault with the idea, just as I had earlier in the day. It seemed a good way to deflect the suspicion I’d started to feel coming from him. I reasoned that if it appeared to him that I believed wholeheartedly in their abduction having already taken place a week previous, it’s unlikely I would be implicated either now or in the future as having anything to do with the abduction I assumed was taking place as a result of my phone call. And of course her husband’s being found only lends more credibility to my story, though Arnault still seems to look at me darkly, and the whole thing has grown much larger and more convoluted than I signed on for.

So it seems the best thing to do is to hurl this phone into the chuck, but that leaves me without my line of contact to Jeremy, and so it leaves me with far less possibility of manipulating things as they arise. If he’d answer my calls I might decide. I might be able to learn something in what he has to say, or in how he says it, which could give me a sense of what’s gone on with Miriam and what might be happening in the future. But he’s not answering, and so I can’t bring myself to toss the phone overboard, not yet, uncomfortable as I am in knowing that by not doing so I’m allowing Jeremy Gibbon to follow this boat’s every course of direction. As the tech-geek informed me, the sensor is hardwired into the phone in such a way that it would be complicated to remove it without considerable expertise. He may have been trying to milk me, but I’m not willing to risk it.<

br />

So I’ll keep the thing, for now, the sensor intact. It’s against the better judgment of any good marine engineer to discard a potentially useful tool. And it would be untrue of me to say that the removal of Anna’s husband from this boat, and even of her son, would be unwelcome. It might even be, after all, the overriding reason I keep this phone with me. With Miriam having already rejected me, and perhaps now no longer even alive, Anna may be the last woman I meet in this god-forsaken life who carries the sea as she does inside her, in whom I could so easily swim and sink and drown.

•

This is the first night since our voyage began that Anna hasn’t come to see me. I’ve been waiting in the dim light of my room for hours. The smoke suspended over me makes the light even dimmer, and though I’m tired in my body my mind won’t rest. Her husband must have finally awoken. That’s the only reason she wouldn’t have come. The thought of it lights a flame in my chest.

She’s spoken often of her husband over the past couple of weeks. She said the other night she didn’t know what she’d do if we didn’t find him, and all I could think was that I did, that I knew exactly what she should do. But I’ve had so little experience in speaking of matters of the heart that all I could do was listen and offer her another smoke like I was offering her my life, though I know she didn’t sense it as such. I was sure her husband would never be on this boat, especially then, days after I’d called Jeremy with the EPIRB coordinates. So I thought it best to just be there for her, to go through it all with her, be her confidant. I thought there would be time after this was all over to make my feelings known, to find out first who she is and what she desires, so my advances wouldn’t be met with the same rejection they received from Miriam.

But now she’s in the medic room with her husband and I’m here with this jealousy burning in me like some fire that’s waited my whole life for the right wind to work as its bellows and is suddenly, unfamiliarly, scorching through me. The sea and the bottle are all-consuming lovers, the kind that take and take and give only the little necessary to keep you coming back for more; this jealousy is not something I’ve known before and the first and only thing I can think to do as it flares through me is eliminate its fuel source, Anna’s husband.

Anyone who says that killing a man is easy is both speaking a great lie and the greatest of truths. The body dies easily if you know how to make it do so. The first time I killed a man was in a back-alley brawl in Djibouti. It was gruesome how I bludgeoned him with my fists and my boots, and when I left him he was still convulsing in his blood and the red dirt of that alley. I only learned many days later that he’d died, but I realized as my mate told me that I’d already known, had already felt him enter the depths of me. It was like his soul had flown out of the body I’d beaten the life from and straight into my own. I’d been carrying the weight of it inside me for days. I still do to this day. Just as I carry the weight of the other men I’ve killed, and all the whales and other animals, too. They’re all heavy inside me. Which is as it should be, I’m certain, but it’s the part that’s hard about the killing, and anyone who says otherwise is lying, or has never taken a life, or is one of those whose soul has passed far into some dark place where nothing, not grief or remorse or love, can reach to.

As for me I’ve felt the full heft of every life I’ve taken, and so don’t think on it lightly when I consider how I might relieve Anna of her husband. But I can tell, can sense, that the love she thinks she has for him is merely the vestige of something which was once with her but is now gone. And I can see how she has built it back up so that it appears as though it has returned, and is with her now, and that she has done so as a means to protect herself from the prospect of losing him to the sea instead of ridding him from her life on her own terms. Control is everything to us humans and Anna is no exception. We’ll go to great lengths against our better judgment and interests to retain it, and that’s what Anna has done in his absence, in the face of his possible disappearance at sea. Somehow, for her, clinging to the notion of her love for him has kept her in control. So now she has to play it all out, and she is doing so right now while I lie here, waiting for her though I know she won’t come, trying to make sense of everything I’ve felt and am feeling. Trying to decide the right thing to do. Which is, in this world, not a simple thing to come to.

I’m not sure of our coordinates, but I know we’re getting close to the Hawaiis now. Arnault asked me tonight to ready the chopper again first thing tomorrow morning. It could be he’s gotten his hands again on the float. It could be Jeremy Gibbon is dead, which would account for his not returning my phone calls. Or it could be Arnault is taking us right into the centre of a shitstorm. Underestimating one’s adversary is the greatest mistake in any fight. It’s why Sea Shepherd lost that two-million-dollar speedboat to the Japanese whalers last winter. Paul didn’t think they had it in them to tear it in two, just as Arnault might not appreciate what Jeremy Gibbon may do now. If he were smart he’d have purged this boat of its crew the minute the float was stolen from Sunimoto. As it is, he’s only mentioned it in passing, as though it were to be expected, a matter of course, while every moment he’s handicapped by my presence still on this boat, by the cellphone in my drawer sending its little signal up to the sky.

I take it from the drawer and put my boots and coat on. As I climb the fo’c’sle ladder up to the deck I’m calculating it all, the money, Anna, the risks of losing both, though neither is actually with me here, in my hands. I take the phone to the edge of the deck and toss it overboard. Now I’ve got nothing but the old sea, my desire for Anna and the ghosts I carry, with a little room maybe for one more now, way down in the darkest part of me, a place I’ve not entered into since I last drank the whiskey, and it occurs to me that if I’m going to do this there’s one thing I’ll have to do first.

•

Arnault keeps his single malt in the galley, in the high pantry cupboards beside the diesel stove. He’s the only one who drinks onboard, aside from the odd nip Smith shares with him some evenings, so it’s as good a place as any for it. I’ve been sober now for a decade, but the first ounce goes down easy. I’d have taken this as a fall, and taken it hard, even a couple of years ago, but something changed for me when I turned fifty. It’s not that I stopped caring, but I stopped being concerned. I’m in the firing range now, and time spent dwelling on what’s past isn’t a luxury I can afford any longer. Back in the days when I fought for the whales I fought always for the future. But the only future I’ve got to look forward to is my own old age, my own being put out to pasture, and I’ve paid my dues to the future beyond that, the one I won’t live to see. So what I work with now is just that, the here and now. One day at a time, as the adage goes.

The Scotch plies me open as it slides down my throat. I light a smoke to temper the rush. It’s like a flood tearing a widening trough in me just as a river does when it swallows its banks, then its entire valley. The fifth ounce is always the sweet spot, where everything comes clear before it disappears into the fog that follows. It’s here I can take the true measure of myself and it strikes me how essential this has been throughout my life. I’ve been hiding under Arnault’s wing for years now because without access to this point of clarity I’m lost, and impotent, and it’s made a coward of me in the world.

An old friend of mine in the program once told me there are cycles to sobriety, just as there is to everything in life, and to deny this, to keep from the drink beyond what is necessary, is to live in stasis, caught in a net of one’s own fear. He’d been in and out of the program for twenty years and he had this unorthodox reverence for the twelve steps and the bottle both. The life worth living, he said, was the one lived skipping from edge to edge. I always thought of this as his own complex denial. But now I’m seeing it in a different light, feeling the liquor opening me in ways and in places I thought lost to the past, and I can see there’s room in me, more capacity maybe than there’s ever been before, and it makes my decision easy

knowing this, so as I pour myself another drink, I take it.

•

I woke up this morning with my resolve unwavering. I’m not one of those men who is of one mind in the night and another in the morning, the liquor worn off. Those are the weakest of men, the kind who have nothing at their core. I quit drinking not because it made me into some sort of monster I’m otherwise not, but because it seemed to be suppressing something in me I wanted to come to the fore. Which I’ve found now, and it makes this kill I’ll make easy. It’s lack of clarity that confounds things in life. Anna doesn’t see me, not entirely, because the father of her son is perpetually cast like a veil before her eyes. I’ll lift it and be standing there before her when her eyes adjust their focus.

I enter the medic room and see him for the first time since Smith and I hauled him in off the deck two days ago. It’s dark in here, a towel tacked over the small porthole and all the lights out. By the hallway light casting in over my shoulder I can see he’s as gaunt still as he was when he first came aboard, his damaged body sunken in on itself. He’s on the edge, and will go easily over, having next to nothing in him to fight for the air I’ll keep from his lungs. I close the door behind me and its little click wakes him. He turns toward the sound and there’s fright in his eyes as he struggles to set them upon me. I walk to the opposite end of the room and take the towel from the window, letting the last of the day’s light into the antiseptic whiteness. I’ll ease him into this and I’ll find out what’s become of Miriam while I do so.

I pull a chair up close to his bedside so he can bring me into focus through his weakness. I’ve been close to death before, much as he is now, stranded in the aftermath of a wicked storm for nearly two weeks alone inside an inflatable life raft on the Indian Ocean. There was no relief in being finally rescued. It gets like that, or at least it did for me. The closer I got to death the more I wanted to finish the journey. I can see that same disappointment in this man’s eyes, the pain of being forced to find desire for life again when death has already been resigned to, and I’m almost inclined to think he might hold the pillow over his own face for me.

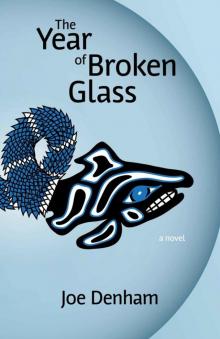

The Year of Broken Glass

The Year of Broken Glass